How I connected with Buddhism

In a blog on the self, I would not want to neglect the philosophical and cultural position that there is no such thing as the self — the Buddhist doctrine of anatman or no-self. In this post I relate the story of my initial encounter with Buddhism.

Skillful Means

In the early 1980s I worked for a magazine publisher in New York City. I was the assistant to the Vice President, which meant next to nothing. Since this particular VP didn’t want anyone to learn how to do her job, I was kept busy with routine, uninteresting tasks.

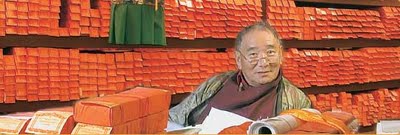

One day on a lunch break, I was browsing in a midtown bookstore (I worked at Sixth Avenue and 50th). I don’t know how I found my way to this particular book — it was one of those it-fell-off-the-shelf-into-my-lap experiences. The title, Skillful Means, meant nothing to me at the time, so there was no reason to select it. The author was a Tibetan lama called Tarthang Tulku (pictured above at Dharma Publishing). The book was about being mindful while doing one’s work, and it turned out to be exactly what I needed at the time.

Writing without a self

The term “skillful means” (upāya in Sanskrit) has a complex meaning in Mahāyāna Buddhism, but, as taught by Tarthang Tulku, skillful means is simply an attitude one can adopt towards one’s work. It includes – among many other things — making creativity the heart of all activity and making work a practice that feels like doing art.

The teachings in this book made my job much more bearable. More importantly, I was so impressed by Tarthang Tulku’s voice – not necessarily what he had to say, but the directness and clarity with which he said it — that I acquired all the books he had published up to that time and read them.

My attraction to his voice may have had something to do with my history of writing. I had just spent several years laboring over one book and beginning another. This had made me aware of what writers reveal about themselves – consciously or unconsciously — by their “tone of voice.” In spoken conversation, tone of voice (sarcastic, belligerent, timid) is easy to hear. In writing, it’s often more subtle. It’s an aspect of self-presentation – for example, my tone of voice can reveal what I think of myself as well as my attitude towards my reader. (My sensitivity to tone of voice may be related to self-conscious blogging (see here and here), but I’ll leave that inquiry for later.)

What struck me about Tarthang Tulku was that there was no ego behind his words. When it came to self-presentation, there was no self to present. This is very rare, and it made a strong impression on me.

Correspondence courses

This was before the Internet, and Tarthang Tulku was in California, where he had founded the Nyingma Institute in Berkeley. The Institute offered various classes by mail – Time, Space and Knowledge (TSK), Kum Nye, the study of classic Buddhist texts, as well as Skillful Means. Classes consisted of monthly readings and assignments, which were sent by mail and sometimes included a cassette tape. For a while I was assisted by a mentor at the Institute, Jack Petranker, with whom I exchanged monthly letters. Today many classes are offered by email.

One of the programs I’ve participated in several times is Kum Nye, a meditative movement and stillness practice. Tarthang Tulku’s version of Kum Nye, which is considered a type of yoga, appears to have originated in medical tantras. He learned it as a child from his father, who was a physician as well as a lama.

I’ve lived in northern California since 1995, so it’s been easy to experience not only the Nyingma Institute, but a wide range of spiritual practices (Amma, Diamond Heart, Adyashanti, Ananda, Tibetan Qigong, lots of yoga and various movement practices — I even became a teacher of a movement practice). But I consider the teachings of Tarthang Tulku my home base when it comes to Buddhism.

Tarthang Tulku on competition

Here is an excerpt from Skillful Means on competition, a subject close to my heart (see Can we think outside our culture: My Chinese horoscope).

Competition is found in almost every aspect of life. It is the foundation of most of our sports and games, and it plays a large role in business and our personal lives as well. We are continually concerned with who is the fastest, the smartest, the richest, the best. Among scholars, philosophers, and religious leaders, there is constant striving to be more correct, more original, more devout than anyone else. Even lovers work to outdo each other in their amorous skills.

When we compete without thinking to ‘win’, valuing everyone’s efforts equally, competition can be a very positive/motivating force. It can teach us to appreciate our abilities more deeply, and it can lead to an appreciation and a greater respect for the capabilities of others as well. Unfortunately, because competition is the road to success and power in business, politics, and education, even in social interactions, it is usually used to gain selfish aims. Instead of competing with others, we compete against them. When competition becomes combat, it loses its power to inspire, and becomes instead a form of pressure which creates disharmony in our minds and senses, upsetting the natural balance of our lives.

As we compete with one another to succeed, we widen the distance between ourselves and others. We become so intent on our quest for achievement that it becomes easy to ignore the feelings and hopes of those around us. We become willing to manipulate others to prove we are better than they are, and soon the aspirations and efforts of even our friends are undermined. The enmity and suspicion that result from competing in this way can create barriers between ourselves and others that are beyond our ability to overcome.

The urge to win causes us to focus on the negative rather than the positive qualities of those around us so that we will appear more successful; we learn to point out the failings of others to make ourselves look superior. But what is the cost of this pattern? Do we benefit in the long run from treating others like this? Are we really better than they are, or are we standing on false ground? Though we may laugh at others, if we faced ourselves honestly, what would we have to laugh at? …

Competition can become so ingrained in our attitude that we believe it to be a natural human quality; but actually we learn it at home, in school, at our work. We teach it to our children, pushing them to compete because we want them to be more successful than we have been. This pressure to succeed, however, often only teaches our children to fear failure, a fear which gradually undermines their self-confidence and actually prevents them from succeeding. Perhaps we urge our children to compete because we believe it will stimulate their motivation. But motivation that emphasizes success alone cannot encourage the well-integrated development of all their abilities.

I wonder if Buddhism appeals especially to those who dislike the competitive, highly individualistic, achievement-oriented nature of American culture? Zen Buddhism attracted American followers starting in the 1960s and Tibetan Buddhism in the 1970s. The explanation for Buddhism’s appeal is surely multi-faceted. Please leave me a comment if you’re aware of any social scientists or historians who have written on this.

Related posts:

My so-called writing life

The self-conscious blogger

Learning in public

Can we think outside our culture: My Chinese horoscope

Image source: Dharma Publishing Store

References:

Tarthang Tulku, Skillful Means: Patterns for Success

Tarthang Tulku, Time, Space & Knowledge: A New Vision of Reality

Tarthang Tulku, Kum Nye Relaxation: Theory, Preparation, Massage

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.